By Cynthia Chung [Originally published on The Cradle in January 2022.]

‘A crisis is an opportunity riding the dangerous wind.’ So says a Chinese proverb, and nowhere is this truer than in crisis-ridden West Asia, now a major focus of Beijing’s BRI vision to bring infrastructure, connectivity and economic growth to this struggling region.

West Asia’s winds have changed. When Syria began 2022 by joining China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), it became the 20th Arab country that Beijing has factored into its grand connectivity vision for Asia, Africa and Europe.

The Arab states in China’s sights include those that have already signed deals, and others with proposals in hand: Egypt (2016), Sudan (2018), Algeria (2018), Iraq (2015), Morocco (2017), Saudi Arabia (2018), Yemen (2017), Syria (2022), Somalia (2015), Tunisia (2018), UAE (2018), Libya (2018), Lebanon (2017), Oman (2018), Mauritania (2018), Kuwait(2018), Qatar (2019), Bahrain (2018), Djibouti (2018), Comoros.

The ambitious connectivity and development projects the BRI can inject into a war-torn, exhausted West Asia have the ability to transform the areas from the Levant to the Persian Gulf into a booming world market hub.

Importantly, by connecting these states via rail, road, and water, the foreign-fueled differences that have kept nations at odds since colonial times will have to take a back seat. Once-hostile neighbors must work in tandem for mutually-beneficial economic gains and a more secure future to work.

And money talks – in a region continuously beset by war, terrorism, ruin and shortages.

Rebuilding Syria and linking the Four Seas

On 12 January this year, Syria officially joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The timing of this decision dovetails with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s whirlwind tour of West Asia this past spring and summer, beginning with the signing of the $400 billion Sino-Iranian 25-year Comprehensive Cooperation Plan.

In turn, President Bashar al-Assad’s re-election in May last year opened the door to a seven-year Sino-Syrian partnership in the reconstruction of Syria, to relink it to the Mediterranean and Asian markets.

The task will be extensive. The cost of Syria’s reconstruction is estimated to be between $250 and $400 billion – a massive sum, considering Syria’s 2018 total budget was just less than $9 billion.

Nonetheless, Syria has much to offer and China has never been reticent over long-term investment strategies, especially when much can be gained in stabilizing regions that include core transportation corridors.

Syria’s geographical location has been a center for trade and commerce that dates back centuries.

Today, it offers a crucial bypass from the choke points represented by the straits that separate the South China Sea from the Indian Ocean (Malacca, Sunda and Lombok), now controlled by a heavy US presence.

The location of Syria is of central importance to the trade routes through the Five Seas Vision, which was officially put forward by the Syrian president in 2004.

As Assad explained this vision:

“Once the economic space between Syria, Turkey, Iraq, and Iran becomes integrated, we would link the Mediterranean, the Caspian, the Black Sea, and the Gulf … we are not only important in the Middle East … Once we link these Four Seas, we become the compulsory intersection of the whole world in investment, transport, and more.”

The Latakia Port will be crucial to the Five Seas Vision, and will likely be the first primary focus for heavy Chinese investment, with the potential to become the Eastern Mediterranean’s largest port facility.

Iran has a lease on part of the Latakia Port and has a preferential trade agreement with Syria, while Russia has a base at the nearby Tartus Port, roughly 85km south of Latakia.

Latakia provides access to the Black Sea via Turkey’s Bosphorus (Strait of Istanbul), and access to the Red Sea via the Suez Canal. Russia has free trade facilities at the nearby Port Said in Egypt.

From there, vessels can enter the Persian Gulf, under the protection of another Russian facility at Port Sudan, through the Suez Canal.

Goods can then be shipped onto Iran, which connects to the Caspian Sea from the Chabahar Port via the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC).

From the INSTC transport corridor, it is a short journey to Pakistan, India, and ultimately to China.

Reviving routes and expanding ports

Lebanon’s Tripoli port, 20 miles south of the Syrian-Lebanese border, will also be at the center of BRI investment, if the country’s muddled political rivalries allow for it. The port can play a vital role in the reconstruction of Syria – which Washington seeks to thwart – with plans to revive the Beirut-Tripoli railway as part of a wider network that would incorporate Lebanese and Syrian railway systems into the BRI.

China is also looking to help establish a Tripoli Special Economic Zone as a central trans-shipment hub for the eastern Mediterranean. Plans are underway for the China Harbor Engineering Company to expand the Tripoli port to accommodate the largest freighters.

China has helped to expand the Mouawad airport, about 15 miles north of Tripoli, transforming it from a predominantly military base to a thriving civilian airport.

In 2016, the year that Egypt joined China’s BRI, President Xi Jinping visited Egypt, and the two countries signed 21 partnership agreements with a total value of $15 billion.

China Harbor Engineering Company Ltd has been cooperating with Egyptian companies in the construction of new logistic and industrial areas along the Suez Canal.

In addition, the China State Construction Engineering Corporation has been working on the construction of a new administrative capital 45km east of Cairo, valued at $45 billion. These projects will work to further facilitate integration into the BRI framework.

The case of Yemen, which joined the BRI in 2017, remains a challenging one. China has done much to invest in Egypt’s Suez Canal and the Djibouti Port, which connects with the Addis Abba-Djibouti railway.

Djibouti, Ethiopia and Sudan all joined the BRI in 2018, while Somalia had been on board since 2015. China established its first overseas military base in Djibouti in 2017, giving it access to the key maritime choke point in the region. Yemen stands to gain much with its strategically placed Port Aden.

China’s ambassador to Yemen, Kang Yong, said in a March 2020 interview with Yemeni news outlet Al-Masdar that China considers all agreements signed between the two countries prior to the onset of the 2015 war as still valid, and will implement them “after the Yemeni war ends and after restoring peace and stability.”

Although both China and Russia have made the point that they will not directly intervene in regional politics, it is clear where both nations stand in their orientation, as gleaned from the rapid ascension that has been granted to Iran in recent months.

This past September, Iran was admitted as a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), while Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Qatar were admitted as SCO dialogue partners, joining Turkey.

Over the past year, Iran has quickly gained high regard and is now considered the third pillar to the multipolar alliance of Russia and China, increasingly referred to as RIC (Russia-Iran-China).

On 21 September, officials from Saudi Arabia and Iran met for the fourth round of talks aimed at improving relations, and although the process remains slow, it looks increasingly possible that a peaceful resolution can be reached.

Returning to Syria’s Five Seas Vision, Iraq also has a crucial role to play in this game-changing program.

The office of the Iraqi prime minister stated last May that “negotiations with Iran to build a railway between Basra and Shalamcheh have reached their final stages, and we have signed 15 agreements and memoranda of understanding with Jordan and Egypt regarding energy and transportation lines.”

The railway is part of Syria’s reconstruction deal. The 30km Shalamcheh-Basra rail line will connect Iraq to China’s Belt and Road lines, as well as bring Iran closer to Syria. Basra is also linked to the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC).

The Shalamcheh-Basra rail link will make it possible for Iran to send various commodities, such as consumer goods, construction materials, and minerals through the railway from Tehran to Shalamcheh and then to Basra, and finally to Al Qaim border crossing between Iraq and Syria, which was re-opened in September 2019 after being closed for eight years due to war in both countries.

Presently, there is no rail link between Al Qaim in Iraq to Syria’s rail station in Deir Ezzor, which is roughly 163km away. This should be a priority for construction. From Deir Ezzor, Syria’s existing rail line connects to Aleppo, Latakia, Tartus, and Damascus.

On 29 December, the Iranian cabinet approved the opening of the Chinese consulate in Bandar Abbas, China’s first consulate in Iran. It is expected that China will invest heavily in the Chabahar Free Trade and Industrial Zone and Bandar Abbas, Iran’s most important southern sea transportation hub.

The former Iranian ambassador to China and Switzerland, Mohammad-Hossein Malaek, told the Iranian Labour News Agency (ILNA) that Beijing is set to play a leading role in developing the Makran region, the coastal strip along Iran’s Sistan-Baluchestan province and Pakistan’s Balochistan, and where Beijing already has a 40-year, multi-billion dollar agreement with Islamabad to develop the Gwadar port.

Both Iran and Turkey have been intensely engaged with the BRI. The first freight train ran from Pakistan to Turkey through Iran on 21 December last year, after a 10-year hiatus.

This resulted in a major boost to the trading capabilities of the three founders of the Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO), created in 1985 in Tehran by the leaders of Iran, Pakistan and Turkey, and which now has 10 members.

The 6,540km journey from Islamabad to Istanbul takes ten days, less than half the time needed for the equivalent voyage of 21 days by sea. The train has the capacity to carry 80,000 tons of goods.

Within the corridors of cooperation and connectivity

Also in December last year, Javad Hedayati, an official with Iran’s Road Maintenance and Transportation Organization, announced that Iran, Azerbaijan, and Georgia had reached an agreement on establishing a transit route connecting the Persian Gulf to the Black Sea.

This transit route could potentially link with the Islamabad-Tehran-Istanbul Rail (ITI) and further boost connectivity in the region.

The construction work of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline is resuming in the Afghanistan section. The TAPI is a regional connectivity project for supplying gas from Turkmenistan to India’s Punjab to meet regional demand.

The pipeline is expected to carry 33 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year. The 1,814km pipeline stretches from Galkinesh, the world’s second-largest gas field, to the Indian city of Fazilka, near the Pakistan border.

This will be more than enough to supply Afghanistan’s own energy needs as it starts to rebuild and reconstruct. TAPI is expected to facilitate a unique level of trade and cooperation across the region, as well as support peace and security between the four countries: India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Turkmenistan.

The Afghan-Uzbek rail project is another exciting proposal that has recently been under serious discussion. The project would include the construction of a 700km long Mazar-i-Sharif to Herat rail line that would pass through Shiberghan, Andkhoy, and Maimana in western Afghanistan.

If this project materializes, all Central Asian countries, including Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, would be connected to Iran’s Chabahar corridor via western Afghanistan.

The Afghan-Uzbek rail project will be one of the biggest breakthroughs in Asian transport connectivity with enormous implications for the entire region, both in terms of economic prosperity as well as political stability.

Afghanistan, Iran and Uzbekistan have already signed an agreement to develop a trans-Afghan transport corridor.

India is also seeking a railway connection with Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, which would connect Chabahar as a gateway between Eurasia and the Indian Ocean.

Cooperation in the area of connectivity with these countries could also be pursued under the SCO framework.

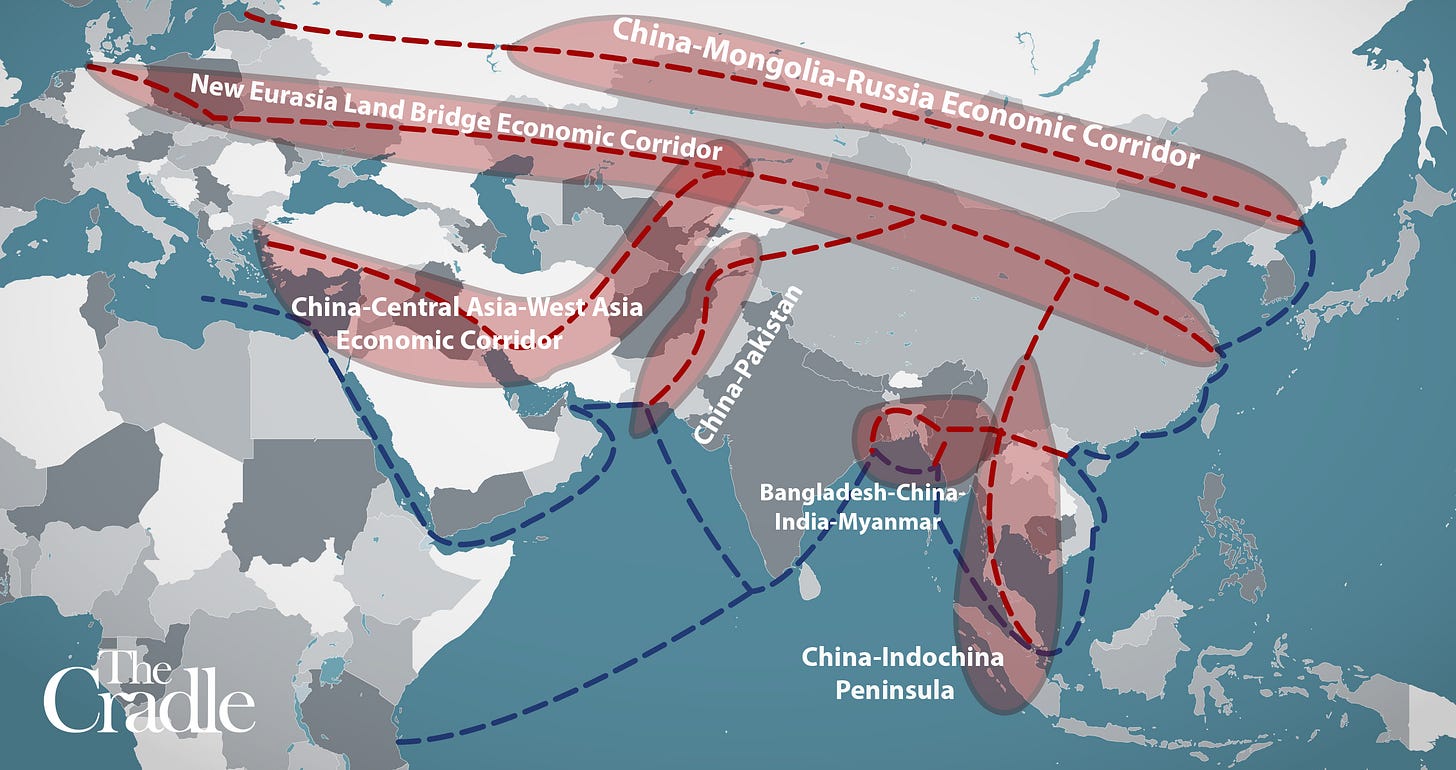

Whether the official title of BRI is present or not, all these development corridors in transportation, industry and energy will participate in the main economic corridors under the BRI framework.

All participant countries in the BRI understand this, and they also know that cooperation is key to mutual beneficence and security.

Meanwhile, Gulf States shun collaboration

Generally, western-backed Persian Gulf countries such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE have done much to sabotage this vein of progress.

Thus far, their involvement in the BRI framework has mostly consisted of exchanging oil for technological resources to diversify their economies. They have not, however, been as eager to participate in collaborative processes with other Arab countries.

Nonetheless, the tides are changing, and one cannot maintain a wealthy island philosophy among this growing framework.

The Gulf States need a market to trade in, so that they can grow and prosper. They are therefore in no position to dictate relations with their neighbors, on whom they will grow increasingly dependent for their survival.

If the Gulf countries – some now dialogue partner states of the SCO – adhere to the guidelines of that political-economic-security organization – funding and support of Islamic terrorism is expected to slowly die out.

This would be the most effective way to isolate the attempts of the west to instigate chaos and division within West Asia.

With the BRI and Eurasian Economic Union framework working in tandem, those who are willing to abide by the multipolar framework of a win-win cooperation will make the quickest ascensions.

And those who sluggishly cling to old prejudices and outdated orders will only sink into irrelevance.

The Rising Tide Foundation is a non-profit organization based in Montreal, Canada, focused on facilitating greater bridges between east and west while also providing a service that includes geopolitical analysis, research in the arts, philosophy, sciences and history. Consider supporting our work by subscribing to our substack page and Telegram channel at t.me/RisingTideFoundation.

Also watch for free our RTF Docu-Series “Escaping Calypso’s Island: A Journey Out of Our Green Delusion.”

As always, the giant shadows over all this are the evil intentions of the US/UK empire run by the banking cartel, hellbent on ensuring its continued world hegemony. Likely they are working closely with Gulf states to keep them from embracing the BRI. It's all about keeping what they have and not letting puppet countries leave the empire's clutches.

The realization of this infrastructure will do much to help the people in these countries. This resulting benefit will be reflected in increased land values. The tragedy of this is that all this land is in private hands and the increase in value will all be pocketed by these few land owners. This increase in value should go to the communities to maintain the infrastructure and invest in other community needs. If this increase in value is used to the benefit of the communities then those that work, produce and provide services need not be penalized with taxes.