By Gerald Therrien

The Qing government tries to end the Opium War

Recently, I began to read a fascinating story about the opium wars in China – ‘Lessons in ambivalence: The Shanghai Municipal Council’s opium policies, 1906–1917’, by Yong-an Zhang and Yilun Du, as I try to piece together a glimpse into the modern history of the North Atlantean attacks against China and its philosopher-president Xi Jinping.

Before I could fully appreciate the content of that essay, I realized that I first had to first study the ‘unequal treaties’ that overturned the Qing government’s protectionist ‘Canton System’, that it had previously used to control its foreign trade, and how the British and the French were allowed their own ‘settlements’ in Shanghai – where the British and French governments could exert their influence, but where the Qing government had no authority over these ‘so-called’ self-governed ‘settlement’ enclaves!!!

By 1863, the British Empire’s International Settlement’s Shanghai Municipal Council [SMC] decided that since it was impossible to eradicate vices, it would regulate and tax the opium houses (and brothel houses and gambling houses) – making it legal to buy and sell opium, and of course, the demand for opium greatly increased. This British (and American) International Settlement became a kind of free-trade-zone for opium sales and consumption.

But then on 30th November 1906, the Qing Council of State [Zhengwuchu] drafted ‘the Regulations of Forbidding Opium Smoking’, that banned smoking opium and planting poppy, and that would close all opium houses within 10 years! And then, by 1907, under pressure from the Qing government, the British government agreed to reduce the import of opium into China until it could be eliminated by 1917.

This policy placed the Qing authorities in direct opposition to the ‘so-called’ independent SMC – whose chairman at that time was Henry Keswick, of the Jardine Matheson conglomerate! It would seem that the SMC wasn’t all that independent, but was more along the lines of the East India Company.

Anyway … all 700 opium houses in the Qing-controlled city of Shanghai were shut down, but the 1600 opium houses in the International Settlement of Shanghai were not. However, the SMC did agree to stop issuing any new licenses for opium houses.

Helping the Qing government was the Shanghai Missionary Association, that began petitioning the SMC to close all the opium houses in the Settlement area, and they also approached the International Opium Commission, that had been convened in February 1909 in Shanghai.

The SMC finally agreed to close the opium houses in 6-month, 25% stages, so that by the end of 1909, all opium houses were shut down!

However … the opium shops that sold opium for private use at home would still be open! And the issuing of opium shop licenses (at a higher fee) increased, as did the income for the SMC!

By November 1911, the Qing dynasty would no longer exist. Was this in fact a regime change, that was launched by the foreign powers, in order to protect their opium trade income, and with the purpose of dividing China up into a number of competing provinces that would make it easier for them to control?

[The implications of this possibility will be developed in a separate essay]

The Shanghai Missionary Association continued its campaign against the SMC’s pro-opium policy, until finally the SMC agreed, once again, to a phased closing of the opium shops in 6-month 25% stages, until the shops were finally shut down by 1917.

Rather than stopping the trade, this act merely drove the opium trade underground.

Chiang, working on the Green Gang

Another piece of evidence emerged as I next found myself looking into the control of the drug trade in China. This research led me to an interesting essay titled ‘Shanghai Gangsters: The Big Eight Mob’, and how the Green Gang came to run it.

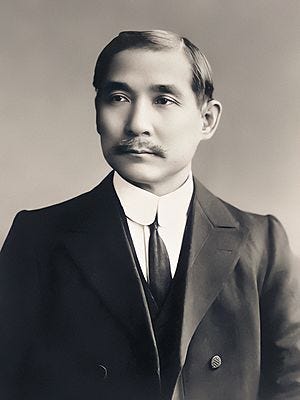

During the Xinhai Revolution in China in 1911, delegates from the different provinces of China met to frame an outline for a Provisional Government, and elected Dr. Sun Yat-sen as Provisional President of this new republic. However, hoping to avoid a civil war between the revolutionaries and the Beiyang army, it was agreed that Yuan Shi-kai, the former minster of the Beiyang army, would become the President. Yuan would be dependent on foreign loans to finance the Beiyang army.

After National Assembly elections, Dr. Sun’s ‘Tongmenghui’ party joined with five other smaller parties to form the ‘Kuomintang’. But when the Kuomintang Premier, Song Jiaoren was assassinated in 1913, and after Yuan began to replace Kuomintang provincial governors with his corrupt Beiyang allies, then the southern provinces declared their independence.

When this ‘Second Revolution’ was defeated, Yuan Shi-kai dissolved the National Assembly and ruled China through the provincial military governors. Dr. Sun and most of the Kuomintang leaders were then forced into exile.

In order to maintain foreign support, in May 1915, Yuan Shi-kai signed the ‘15 Demands’ with Japan, that awarded the German territories in Shandong province to Japan – territories that the allies, Britain and Japan, had quickly seized at the start of World War 1.

When Yuan declared himself ‘Hongxian Emperor’, the southern provinces again declared their independence, and the ‘National Protection War’ started. Yuan was forced to abdicate, but remained President of China. Yuan died soon afterwards, and upon Yuan’s death, the southern provinces rescinded their independence. At this moment, Li Yuanhong became the new president, and the National Assembly was reconvened.

During a dispute over whether China should enter World War 1, a failed attempt was made by Zhang Xun to dissolve the National Assembly and to restore the Qing Emperor. Li resigned and the government came under the control of rival factions of the Beiyang army. This launched a dark period of modern history known as the ‘Warlord Era’.

Now, back to the opium story.

The Qing dynasty’s anti-opium campaign had led to the near eradication of opium growing in China. Sadly, due to the resulting political chaos, provincial military governors and warlords re-introduced the opium trade to raise revenues.

In Shanghai’s British-controlled International Settlement, China’s trade was controlled by the crooked Chief of the Chinese Detectives in the Shanghai Municipal Police – Shen Xingshan, and in the French Concession, the trade was controlled by another crooked Chief of Chinese Detectives, Huang Jinrong.

Under the watchful eyes of the French and the British, the smuggling of opium into Shanghai would ironically be controlled by the Anti-Smuggling Squad and the opium merchants from Canton as well as British-controlled Hong Kong. Within a short time, the drug economy came to be run by the Green Gang, who like all mafia operations also controlled China’s prostitution racket as well.

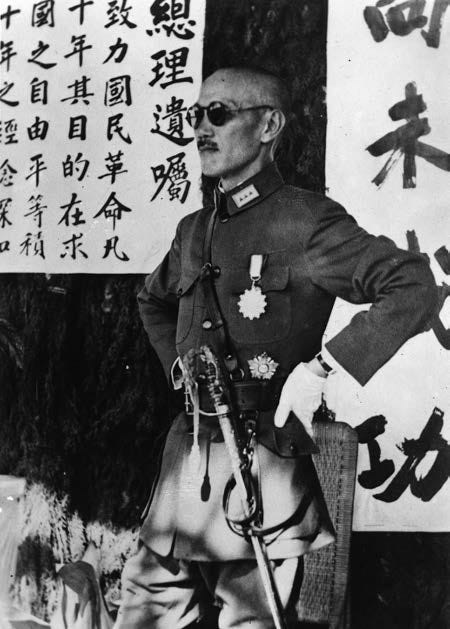

Chiang Kai-shek had joined the Green Gang as far back as 1908, becoming a combination of anti-Manchu revolutionary and gangster – learning the ropes of murder, extortion, armed robbery, and other crimes. Chiang was known for his violent temper, heavy drinking and carousing, while also becoming life-long friends with Du Yuesheng – who became the head of the Green Gang.

Du Yuesheng would become the most anti-communist person in all of China, and financed Chiang’s political career with opium money.

Lenin, Sun and Mao

Although the attempt to establish a new Hongxian dynasty by Yuan Shikai in 1916 had failed, as had the 1917 attempt to restore the old Qing dynasty by Zhang Xun, Dr. Sun Yatsen realized that the attempt to establish a republic of China was also failing. The republican efforts had devolved into a fractionalization of the nation into provincial military governors and/or warlords who preferred maintaining their own provincial control under a decentralized government, instead of uniting their efforts (while loosing some personal freedom) under a strong republic. Making this messy situation even more complicated, whichever clique happened to controlled the capital at Beijing at any given moment, found themselves receiving official recognition of foreign powers – and international loans.

It was at this time, that Dr. Sun “telegraphed Lenin … congratulating him on the relentless struggle of the revolutionary party in Russia and expressing the hope that the Soviet and Chinese parties might join forces in a common struggle”. [from ‘Sun Yat-sen, Frustrated Patriot’, by C. Martin Wilbur, p. 114]

Dr. Sun would enquire extensively “about the Russian Revolution, the development of Soviet republics, the New Economic Policy, the type of propaganda used in Soviet Russia, and the political training of the Red Army.” [ibid, p.119]

With this start of cooperation between China and Russia, Dr. Sun would also begin working on his ‘International Development of China’. This widely read book featuring Dr. Sun’s grand design for an industrial China, liberated of the shackles of poverty and war with thorough outlines of great infrastructure projects to harness the hydroelectric power of its rivers, create roads and rail to integrate the vast nation, and initiate anti-inflationary loans towards long term development.

In contrast to Dr. Sun’s optimistic vision of 1919, the signatories to the 1919 treaty of Versailles, had a different idea of China’s fate, and decided to award Japan all German territories in Shandong province – instead of returning them to China. When news of this reached China, it sparked a new wave of student protests across the country.

“One of the leaders of the student movement in Peking was a mild intellectual named Ch’en Tu’hsiu, dean of the College of Letters at Peking University, where Mao Tse-tung worked in the library” [from ‘The Soong Dynasty’, by Sterling Seagrave, p. 148]

Chen would be arrested for distributing pamphlets denouncing the government dictatorship (as well as a thousand students), was imprisoned for three months, and he then resigned from the university and moved to Shanghai.

“In Shanghai, Ch’en Tu-hsiu and his group of rather harmless and uncertain intellectuals decided that the doctrines of Lenin and Marx were appropriate for the situation that had developed in China … in the middle of July 1921, thirteen men gathered discreetly … The men were delegates to the First Congress of the Communist party of China. One of them was Mao Tse-tung.” [ibid, p.149]

The meeting, however, was suspiciously spied on by the Green Gang. What could the wealthy opium traders find so fearful about these 13 poor students?

Dr. Sun was in Shanghai at that time too, and it was also Dr. Sun’s view that “China must go through another revolution to sweep away the monarchist and military groups in power”. [from ‘Sun Yat-sen’, by C. Martin Wilbur, p.116]

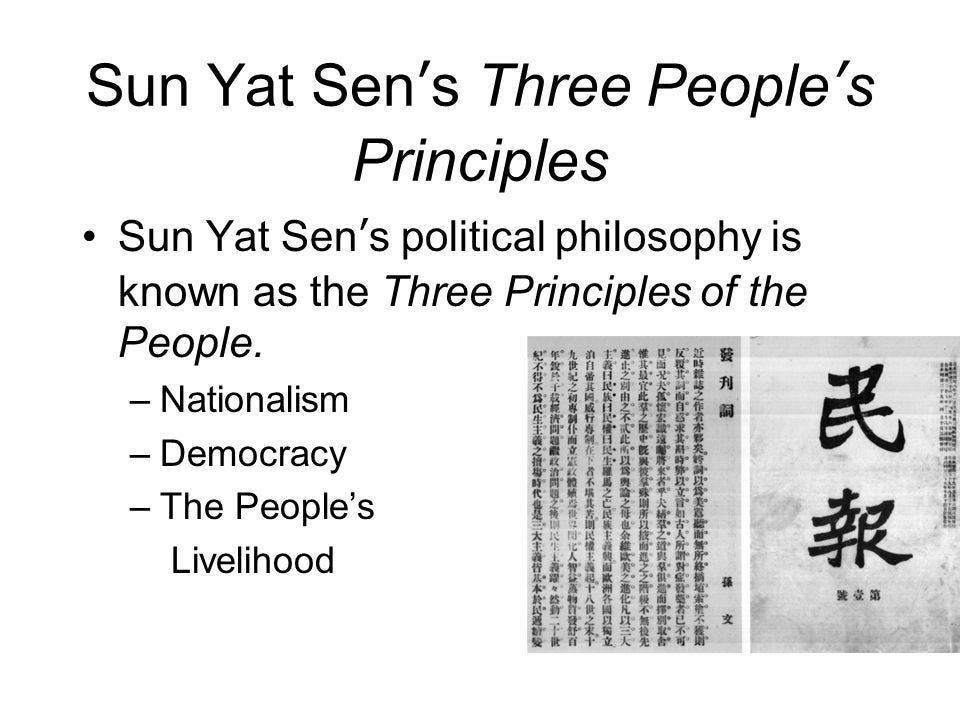

And so, he began working on another book ‘Reconstruction of the State’ – and one of the chapters would be about three ideas – ‘San Min Zhuyi’. This would be Dr. Sun’s formulation of Abraham Lincoln’s principle of government ‘For, By and Of’ the people.

And what could be so fearful as a poor idealist writing a book about ideas?

Chiang, the Green Gang’s inside man

In late 1920, Dr. Sun left Shanghai and returned to Guangzhou, where by May 1921, he became the newly-elected president of the South Chinese Republic, and he began working on his plan for a Northern Expedition. Since the foreign powers only recognized the clique that occupied Beijing as the official government of China, Dr. Sun saw that without defeating the northern Beiyang warlord cliques who occupied Beijing, there was no way to unify a republican China.

Dr. Sun’s plan was opposed by the Guangdong military governor (warlord) Chen Jiongming, who feared that if he left for a northern expedition, then a rival warlord would take over his province. He preferred the scheme of a decentralized China with the warlords keeping control of their separate provinces.

At that time, in early 1921, an office of the Soviet news agency ‘Rosta’ was set up in Guangzhou, where Dr. Sun could learn more about developments happening in Russia, and in June, Dr. Sun received a letter from Georgii Chicherin, the Soviet Union’s foreign minister, wishing to open up trade relations with China and to ‘enter resolutely the path of good friendship’. [from ‘Sun Yat-sen’, by C. Martin Wilbur, pg. 118]

In December, Dr. Sun met with J.F.M. ‘Maring’ Sneevliet, a Dutch agent of the Cominterm, who was secretary of the Commission on National and Colonial Questions – “in which Lenin set forth his famous theses that laid the theoretical basis for the cooperation by communist parties in colonial and semi-colonial countries with bourgeois national liberation movements.” [Ibid, pg. 119]

‘Maring’ proposed that Dr. Sun’s Kuomintang party should also include peasants and workers; that Dr. Sun should set up a military academy; and that Dr. Sun’s party should cooperate with the communist party.

In May 1922, it was decided that Dr. Sun would lead the Northern Expedition and that Chen Jiongming would stay and look after Guangdong – in case of any British-launched actions against the rear of Dr. Sun’s army. But no sooner had Dr. Sun left Guangzhou to take command of his army in Shaokuan, than Chen marched his troops into the city and took over the government. Dr. Sun left his army and rushed back to the city with only his bodyguards, while sending a telegram to Chiang in Shanghai to come to his assistance. But Chiang did nothing.

Then Chen sent his troops to attack and to kill Dr. Sun, who barely escaped to a Kuomintang gun boat where he sent another urgent telegram to Chiang. Chen would burn Dr. Sun’s residence, along with all his books and writings! With Dr. Sun having escaped and safely on board the ship, Chiang now joined him on this floating garrison for the next two months – slipping way at night to get food, and even taking his turn to sweep and scrub the deck!

“It is hard to believe that he came to the aid of Dr. Sun and performed this uncharacteristic toil out of genuine chivalry. Up to this point he had walked out on Sun at every twist and turn. He did not respond to Sun’s first urgent call for help, and took his time responding to the second. In view of what happened later, and from a careful appraisal of his letters, it is evident that Chiang was sent to Sun’s rescue by his right-wing cronies in Shanghai, because they could see more clearly than he that this was the chance of a lifetime for him to step into the top echelon of the KMT. Whoever helped the quixotic old revolutionary by becoming his Sancho Panza at this dark moment of misfortune could earn his undying gratitude. Chiang’s cronies were becoming deeply concerned about Dr. Sun’s growing fascination with Soviet Russia, and with Marxism. Their alarm may have been exaggerated, but they soon had written evidence that they were correct…

Impressed as he was intended to be by Chiang’s display of mulish steadfastness and humility, Dr. Sun decided that the young military man was ready for the big jobs of the revolution … Chiang’s meteoric rise was about to begin.” [from ‘The Soong Dynasty’, by Sterling Seagrave, pg. 171-172]

Dr. Sun meets a Jewish Canadian

Before Dr. Sun’s house in Guangdong was burned down by General Chen, in the prior search, a few papers were found (that were not burned like all his other papers) – papers that showed Dr. Sun’s ‘secret conspiracy with the Bolsheviks’, and these papers were printed in the Hong Kong Telegraph, to try to discredit Dr. Sun.

In Washington, D.C., the head of the Bureau of Investigation, William Burns, “was especially anxious to know if Sun Yat-sen was a Jew, if he had any Jewish connections or backing from any international Jewish interests”.

Burns was among a large network of agents shaping a new secret police apparatus in North America and Europe who promoted that logic that Jewish people – as well as Germans (since Karl Marx was a German) were part of a communist conspiracy who wanted to overthrow order. This was provable in their minds, since Jews played a big role in starting labor unions- which were treated by all Rockefeller cartels as troublesome disruptors of “order” in the first half of the 20th century.

The director of naval intelligence replied to Burns’ accusations of Dr. Sun writing:

“there is nothing to indicate that he is in any way connected with Bolshevik or Radical movements. He has been termed a Radical and is called a Radical by conservative Chinese, but his radicalism consists in visionary schemes for the economic development of China far beyond her present requirements, the needs of the immediate future, and her financial sources.” [The Soong Dynasty, by Sterling Seagrove pg. 172]

However, Dr. Sun did hire Morris Cohen, a Jewish Canadian, as his body guard! Cohen was born in Poland, grew up in London, and was then shipped off to Canada.

“He was a talker in a traveling circus, peddled questionable goods, and plied his trade as a card sharp…

One evening he walked into a Chinese restaurant-cum-late-night-gambling-den in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. There he stumbled right into the middle of an armed robbery.

‘I saw it was a holdup,’ he later recalled, ‘but I wasn’t heeled – that is, armed – and I had to be careful. I closed in till I was too near for him to use his rod and socked him on the jaw. The fellow was out for the count.’

Such an act was unheard of. Few white men ever came to the aid of a Chinese man in early 20th century Canada. As a Jew, though, Cohen felt an affinity for the Chinese underdog. He knew what it was like to be an outsider, someone who society shunned.

Cohen’s selfless act immediately won him the respect of the Chinese community. His new Chinese friends spotted him wagering money and soon asked him to join the Tongmenghui, the political organization of the revolutionary leader Dr. Sun Yat-sen, which a few years later developed into the Guomindang. Cohen became a loyal member, learned of Sun’s teachings, regularly attended lodge meetings, started speaking at some of the get-togethers and gave generously from his gambling earnings to various funds.”

After his enlistment and serving in the Canadian army in WWI, Cohen made his way to Shanghai in 1922, and “he used his Guomindang connections and polished salesman ways to wrangle an interview with Dr. Sun and a job as a bodyguard to the leader and his wife, Soong Qingling.

As an aide-de-camp to Sun, Cohen quickly became one of the leader’s main protectors … He helped supervise the other bodyguards, trained the men to box, taught them how to shoot, all the while thwarting attempts on Sun’s life.”

[from ‘Two-Gun Cohen: Artful dodger turned Chinese legend and hero of Israel’, by Daniel Levy, Jerusalem Post, July 27, 2020]

Who could have foreseen that Morris Cohen, a Jewish-Canadian member of the Kuomintang, with all of his troubled trails and troubled past, would be given the task of guarding one of the most important persons in the world?

Dr. Sun allies with Soviet Russia

While the American and British-backed clique were fighting the Japanese-backed clique for control of Beijing, Dr. Sun, after surviving the assassination attempt by Chen Jingming, emerged as the essential wildcard in China’s struggle for unification against the colonial powers.

As can be seen in a June 25 1922 telegram to Secretary of State, Charles Evans Hughes, from Jacob Gould Shurman, the American minister to China, Dr. Sun was regarded as “the one outstanding obstacle to reunification … Now that nothing remains but the elimination of Sun Yat Sen, not victorious but defeated, it would seem that the undertaking should be left to the Chinese Government if Chen Chiung Ming can not or will not accomplish this.” [from ‘Sun Yat Sen’, by C. Martin Wilbur. pg. 331]

[Note: Schurman was born and educated in Canada, and would become president of Cornell University and later the American minister to China from 1921 to 1925.]

Dr. Sun favored a peaceful reunification with the military cliques, proposing that all the parties disband half their troops and convert them into laborers for public works. But the Americans argued that ‘the only way in which reunification can be brought about is for the foreign powers to intervene effectually and force the suspicious and contending leaders to unite’. [ibid, pg. 142]

Dr. Sun said that since the foreign powers had control of all the revenues of China and they had sent any surplus payments to Beijing, they could simply cut off the payments and easily force an agreement for reunification.

Britain did not want to assist Sun, because ‘he has probably reached some understanding with Bolsheviks, and has coquetted with communism and Indian sedition’. [ibid, pg. 147]

Aaahhh … this great fear of the ‘Anglo-Saxons’, that China might ally with Russian and India, is still so obviously seen even to today!

Not being able to rely on or to trust the British or American meddlers, Dr. Sun began working with the only foreign government that understood and supported his efforts to unify China around the principles of the constitution – Lenin’s Soviet Union.

And Dr. Sun urged Japan to ‘make common cause with the Russians in opposition to the aggression of the Anglo-Saxons’, because he felt there was nothing to fear from Soviet Russia ‘so long as it continues true and loyal to its non-imperialistic policy’. [ibid, pg. 134-135]

The Soviet ambassador to China, Dr. Adolph Joffe, arrived in Beijing and began corresponding with Dr. Sun. They would meet later in January 1923 in Shanghai, and would issue a joint statement of agreement:

“Dr Sun Yat-sen holds that the Communistic order or even the Soviet system cannot actually be introduced into China, because there do not exist here the conditions for the successful establishment of either Communism or Sovietism. This view is entirely shared by Mr. Joffe, who is further of the opinion that China’s paramount and most pressing problem is to achieve national unification and attain full national independence …”

“… the Russian government is ready and willing to enter into negotiations with China on the basis of the renunciation by Russia of all the treaties and exactions which the Tsardom imposed on China’.[ibid, pg. 137-138]

Joffe would write to Moscow that he saw Dr. Sun’s Kuomintang as ‘the only Chinese party with a truly revolutionary platform, a party which served as the meeting point of nationalism and revolution’. [ibid, pg. 133]

Dr. Sun knew that the great enemy of China was not communism, but was COLONIALISM! – something that American president Franklin Delano Roosevelt would also recognize with his alliance with Stalin and with his disagreement with Churchill against British colonialism. Unfortunately, Truman bought into Churchill’s Cold War narrative and believed that somehow the problems in the world were caused by communism and not colonialism.

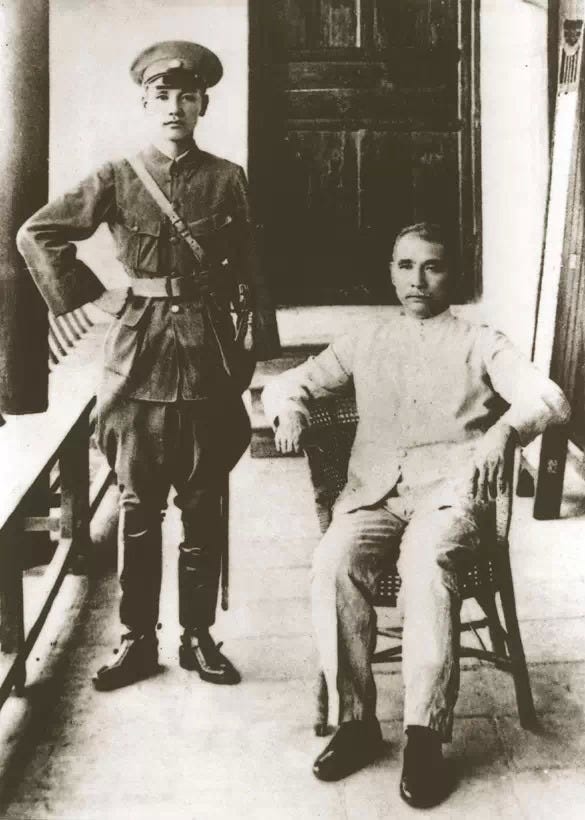

The Early Chiang Kai-shek

Before continuing to explore the structure and growth of China’s Green Gang, and the nationalist efforts to combat this parasite enmeshed inside China’s deep state, it will be necessary to review the personality of Chiang Kai-shek.

In the book ‘The Early Chiang Kai-shek: A Study of his Personality and Politics, 1887 – 1924’, by Pichon P.Y. Loh, a thorough picture of Chiang is painted from the day of his birth on October 31st (Hollowe’en), 1887.

Chiang’s father was a salt merchant who died when Chiang was seven. Sadly, for his mother “the birth of Chiang brought her no joy. He was frequently sick, owing to a frail constitution as well as to mischievous horseplay … by the time he was five – and ‘much naughtier than before’ – she apparently had had enough of him and … committed him to a family tutor, sooner than she had intended … Chiang seems to have found neither identification with his father nor affection from his mother.”

“The bond that developed between the widow and her fatherless son was thus characterized by an ambivalent emotional tension that often burst through the veneer of unsteady calm into uncontrollable passions. Unaccustomed to natural parental love during his formative years, Chiang responded to his mother’s forced affection with an awkwardness and unnaturalness that often assumed extreme, even contrary, forms. Joy found expression in sorrow; ill-omened dreams marked the height of filial devotion.”

Loh quotes the diagnosis of Chiang by one of his teachers, Mao Su-cheng “At play, he would regard the classroom as his stage and all his schoolmates as his toys: he could be wild and ungovernable. But when he was at his desk, reading or holding his pen trying to think, then even a hundred voices around him could not distract him from his concentration. His periods of quietude and outburst sometimes occurred within a few minutes of each other: one would think he had two different personalities. I was greatly puzzled by him.”

Loh continues that “… from the moment of his birth, Chiang sensed psychological rejection and learned instinctively to be distrustful of his social environment … it was a cruel world that laughed at the one thing that was his, his physical appearance … He was incapable of responding normally and in due proportion to a wide range of emotional situations.”

Chiang wrote of himself that:

“In my youth I was naughty and dull-witted and would not subject myself to rules and regulations. And also, because of my humble origin, I was frequently discriminated against and rejected. Having reached manhood, I determined to go abroad for a military education.”

After failing the civil service examination, he sought out a career in the military, and he attended the Short-term National Army School, in Hopei, in 1907, and after passing the examination to be sent for further training to Japan, he arrived in the spring 1908 at the Shimbu Gakko in Tokyo. He graduated at the end of 1910, and then was assigned to the 13th Field Artillery Regiment of the Japanese Army for a year, before he returned to China in 1911.

Loh quotes Tang Leang-li –

“He hurried back to Shanghai, and was at once commissioned by Ch’en Ch’imei, the revolutionary Tutuh [governor] of Shanghai, who was also a Chekiangese, [from Zhejiang province] to command the 83rd Brigade, a band of some 3,000 men recruited from the riff-raff of Shanghai.

He gave his band a severe training, but soon he abandoned himself to a life of intense dissipation. He would disappear for months from headquarters in the houses of singsong girls, and for some reason or other he acquired a fiery, uncompromising temper which weighed very tryingly on his friends.

It was during this period that he became friendly with Chang Ching-chiang, who was to become one of the most sinister characters in the Revolutionary Movement. He also came into contact with the leaders of the secret societies in Shanghai [i.e. the Green Gang], which later on became very useful to him in his dealings with the Shanghai capitalists.”

Here is where Chiang found his future sponsors, like Chang Ching-chiang, Huang Jinrong and the Green Gang.

It was also in Shanghai, that “Not long afterward, Chiang took it upon himself to ‘liquidate’ T’ao Ch’eng-chang, an influential leader of the Restoration Society (Kuang-fuhui) in the Shanghai-Chekiang area and a potential threat to the authority of Ch’en Ch’i-mei.”

Chiang soon fled back to Japan, but by the end of the year, 1912, he returned to Shanghai and would take a concubine named Yao, with her young child, back to his mother’s home in Chikou. “It was one big happy family: his tyrannical mother, his forlorn wife and bull-headed son, and the exquisite Yao.” [The Soong Dynasty, by Sterling Seagrave, pg. 161]

Chiang had been married at age 14, by parental arrangement, to a village girl named Mao Fu-mei, and just before Chiang left for Japan, they had a son Ching-kuo. “According to the young woman’s own testimony, Chiang treated her violently and frequently beat her. She was doubtless relieved when he left.” [ibid, pg.155-156]

Later, Chiang “divorced his original village wife, cast out the chambermaid concubine whom he had only recently installed at the family homestead in Chikou, and married Miss Chen” – a harlot named Chen Chieh-ju. [ibid, pg. 164]

But by 1921, Chiang was planning a strategy for arranging a marriage to May-ling Soong, Madame Sun Yat-sen’s younger sister. When Dr. Sun asked Madame Sun about this “she was scandalized. She would rather, she hissed, see her little sister dead than married to a man, who, if he was not married, should have been to at least one or two women in Canton alone.” [ibid, pg 165]

Aaahh … but being married to Dr. Sun’s sister-in-law would better help Chiang to appear as the heir-apparent to Dr. Sun, during his grab for power after Dr. Sun’s death. While it was described as a marriage of convenience, May-ling would eventually fall in love – with Chiang’s newly-acquired wealth and power. [Some say that they deserved each other!]

Dr. Sun’s Northwest Plan

The foreign powers, of Britain, France, and United States, viewed Dr. Sun as being in rebellion against the military cliques that controlled Beijing – that these foreign powers recognized as the official ruling power of China.

And those same foreign powers supported an international arms embargo against Dr. Sun’s government in Guangdong, and they also denied him any revenues from the foreign-controlled Maritime Customs Service. Additionally, Dr. Sun’s southern army in Guangdong was being checked by British and American gunboats along the Yangtse river, that stopped any attempt for him to march north with his army against the Beijing military government.

Later, by the end of 1923, when Dr. Sun tried to obtain a proper share of the surplus custom revenue dominated by the British Empire, and was prepared to order the custom commissioners to cease sending funds to Beijing and to keep them for local use, the foreign powers sent 16 warships – 6 American, 5 British, 2 French, 2 Japanese, and 1 Portuguese, to stop him.

Dr. Sun informed the British (Sir James Jamieson) that ‘he would be only too glad to be defeated by Great Britain, which then would be responsible for the death of democracy in China’. [from ‘Sun Yat-sen’, by Martin Wilbur, pg. 183]

And Dr. Sun cabled his friends in the United States telling them that “The revenues belong to us by every right known to God and man. We must stop the money from going to Peking to buy arms to kill us, just as your forefathers stopped taxation going to the English by throwing English Teas into Boston harbor. Has the country of Washington and Lincoln foreswarn its faith in freedom and turned from liberator to oppressor?” [ibid, pg. 185-186]

Well … President Coolidge’s answer was to side with the British and the foreign powers against China. At this point, Dr. Sun did not see Soviet Russia as his last hope, but as his only hope!

Dr. Sun had also tried to interest Germany in investing in projects of economic and military reconstruction in China, but because of the Draconian terms of the Versailles Treaty’s reparations, Germany was not able to provide any assistance.

Dr. Sun had dreams of a China-Russia-Germany cooperative alliance that would benefit them all. Was he looking for a flower in the light of good fortune, perhaps?

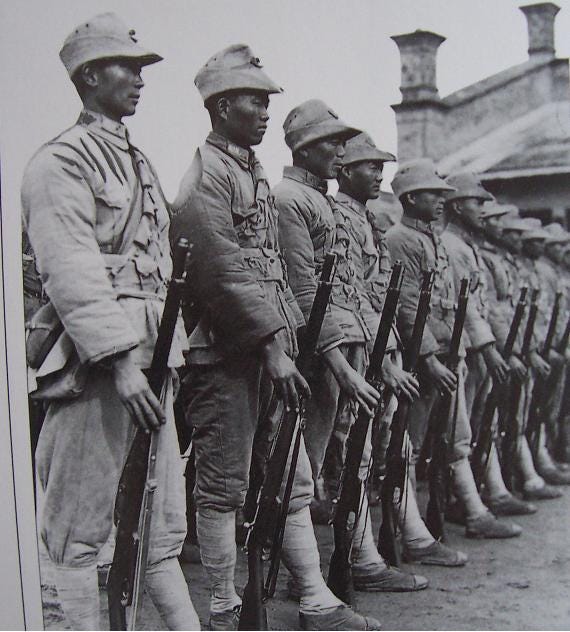

By launching this first ‘United Front’, Dr. Sun sought the help of Soviet Russia, with arms, equipment and especially instructors, to launch his ‘Northwest Plan’ – at the same time as his southern army would move northwards from Guangdong, a northern army would move southwards from Manchuria and Xinjiang, in order to capture Beijing and defeat the military cliques, and to restore constitutional government.

First, Dr. Sun planned a reorganization of the Kuomintang, with a new party platform, a revised party constitution, and a party manifesto – all meant to broaden the base of the Kuomintang, from a party of elitists to a ‘national’ party of peasants and workers too, and second, the creation of a Kuomintang army.

In the summer of 1923, the Third Congress of the Communist Party of China agreed to the offer of Dr. Sun, that members of the Communist party would be allowed to join the Kuomintang – without having to give up their membership in the communist party.

[Note: It was estimated that at that time, the Communist party had maybe a few hundred members, and the Kuomintang had approximately 10,000 members.]

Dr. Sun was inviting a small group of young intellectuals to join his movement, around the ideas that he would put forth in his ‘Three Principles of the People’ – an offer that can be seen in retrospect, as changing the course of human events.

The Communist Party of China resolved that “We should strive to expand the Kuomintang’s organization throughout China in order to centralize all Chinese revolutionary elements in the Kuomintang for the purpose of meeting the immediate needs of the Chinese Revolution … the immediate political struggle naturally means only the national movement, the movement to overthrow foreign power and militarism. Hence, there is need for large scale propaganda, in favor of the National Revolution among the laboring masses in order to expand the Kuomintang which stands for the National Revolution.” [from ‘Documents on Communism, Nationalism, and Soviet Advisers in China, 1918-1927’, by Wilbur and How, pg. 85]

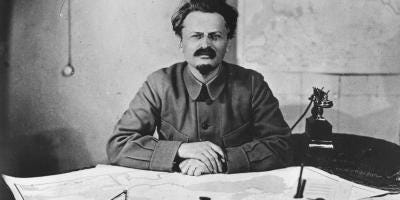

Then in August 1923, Dr. Sun sent a delegation to Soviet Russia, that included Chiang Kai-shek and Wang Teng-yun, plus Sheng Ting-i and Chang Tai-lei (two communist party members), with letters to Lenin, Tchitcherin and Trotsky that “Chiang was to take up with your government and military experts a proposal for military action by my forces in and about the regions lying to the Northwest of Peking and beyond.”

But the Chinese delegation, led by Chiang, would not be meeting with Lenin, who had recently suffered his third stroke, and who would soon die in January 1924. Instead, Chiang would meet with Trotsky, the chairman of the Red Army, and Trotsky replied to Chiang that “Except direct participation by Soviet troops, Soviet Russia will do her best to help China in her National Revolution by giving her positive assistance in the form of weapons and economic aid.”

While Chiang was in Moscow, “he evidently spent most of his time with the Cheka, learning their methods” [The Soong Dynasty, by Sterling Seagrave, pg. 183]

And meanwhile, Mikhail Grusenberg, aka ‘Borodin’, Lenin’s agent in China, would arrive in Guangdong.

Borodin, a Jewish Russian, was born in Belarus and raised in Latvia, where he would join the Jewish Labour Bund and later the Bolsheviks. After being arrested as a party organizer in 1906, he was allowed to leave Russia, and he then moved to the United States, where he went to Valparaiso University, and later ran an English school for Russian Jewish immigrants in Chicago. But after the October Revolution, he returned to Russia in 1918 and resumed his party organizing. After going to Mexico to help establish the Mexican Communist Party, he went to Britain to reorganize the British Communist Party but was arrested and deported back to Russia. He was then chosen by Lenin to lead the mission to China.

Borodin set up his office across the street from the Kuomintang’s headquarters, where he would work closely with Dr. Sun to reorganize the Kuomintang, and where he also worked with Chou En-lai and Ho Chi Minh.

How Chiang went to Moscow

So, how did Chiang come to lead this delegation to Moscow?

It must be kept in mind that one of Dr. Sun’s key problems was that he was ‘ever in need of qualified military personnel’.

When Dr. Sun had first attempted a northern campaign in 1922, Chiang was opposed, arguing instead that first they must consolidate control in Guangdong before making plans for any northern expedition. Chiang said that he faced ‘unceasing provocation and jealousy from certain quarters’ and so he decided to leave for Shanghai.

Less than two months later, Chen Jiongming launched the coup and attempted assassination against Dr. Sun in Guangdong, while Chiang was safely in Shanghai!?!

So, when Chiang finally arrived to see Dr. Sun after his escape to the warship, ‘for one and half months Chiang was in close attendance on Sun’ – attempting to earn his trust, and to dispel some of his doubts about Chiang.

“As none of the party leaders remained on board the Yung-feng, it appears likely that the two men had a unique opportunity to establish a close relationship and their association seems to have been unmarred by bickering or interpersonal tensions.” [The Early Chiang Kai-shek, by Pichon Loh,pg. 72]

After accompanying Dr. Sun back to Shanghai, Chiang immediately left for Ningpo, and Chiang only returned to Shanghai for a few days, where he wasn’t able to see Dr. Sun, but where he did visit his friend, Chang Ching-chiang. Chiang again returned to Shanghai in October, when Dr. Sun would appoint him chief-of-staff under Hsu in Fukien province. Within a month of arriving, Chiang was ready to quit and leave, even after Dr. Sun wrote him that “What rubbish you talk! Since I could not go to Fukien myself, I have entrusted you with the responsibility of punishing the traitors. How could you so quickly think of giving it up like that? Things do not happen as we wish eight or nine times out of ten. Success always depends upon your fortitude and persistence, your disregard of jealousy and hard work. If you give up when there has been no progress within ten days, then you will never succeed in doing anything.”

Chiang left Fukien to return to Shanghai, but after 3 weeks he reluctantly returned, and after another three weeks he left again, refusing to serve under Hsu.

Back in Shanghai, Chiang wrote to Liao Chung-kai that “he mildly reproached Sun for his ‘overly rigid views’, which, Chiang said, had rendered it difficult to ‘manipulate’ otherwise malleable elements in Chinese politics.

Rather than insisting on its own narrowly-defined positions and expecting others to fall in line, the Kuomintang should, he suggested, make it possible to effect working relationships with all factions, or nearly all, provided they did not contradict or detract from the immediate objective of the party.

As long as this central objective—presumably Kuomintang primacy in the power matrix—was kept inviolate, all other issues could be relegated to positions of secondary importance and compromise should be possible … Which should come first for the party—principle or power? … Chiang recommended as the ‘easiest’ and ‘quickest’ means of reaching their objective, was for the Kuomintang to emphasize political power over party principle.” [The Early Chiang Kai-shek, by Pichon Loh, pg. 79 – 80]

For Chiang it was always about power, first and foremost.

However, the reply expressed disagreement, and the view that Kuomintang leadership felt that Chiang’s place was in the military. Chiang was named as one of the thirteen members of the Military Council, and Dr. Sun appointed him chief-of-staff to Dr. Sun’s own headquarters. Again, Dr. Sun was ‘ever in need of qualified military personnel’.

But Chiang refused to go, and after fruitless meetings and urgings, Chiang was permitted to resign both his positions of chief-of-staff – to Hsu and to Dr. Sun, but he kept his seat on the Military Council, and went to Guangdong.

In June, Dr. Sun again made him his chief-of-staff, but a month later Chiang resigned, again – on account of ‘misunderstanding and jealousy’, meaning that he was unable to work with others.

Chiang wrote that “he ‘did not have the natural gifts to be a staff officer’ and might better serve in a military post that allowed him ‘to act summarily without interference from anyone’. For the moment, he would prefer to be assigned to a mission of investigation to Russia, for ‘in my opinion there is nothing to which I can contribute’ in China. If such an assignment could not be brought about, then ‘I will be left with no alternative but to take the negative step of attending to my personal affairs and well-being’.” [ibid, pg. 87]

Chiang would leave the party unless his demands were met, and he returned to Shanghai. A month later, Chiang was asked to a meeting to discuss the composition of the Kuomintang mission to the Soviet Union. Soon, Chiang (the spoiled brat) would be leaving for Moscow with Sheng Ting-i, Chang Tai-lei and Wang Teng-yun.

Chiang in Moscow

Chiang had told Dr. Sun that he might stay in Russia for 5 or 10 years to study, but then after a mere three months, of meetings with Trotsky and of observing the operations of the Cheka, his departure from Moscow was ‘predictably sudden and unexpected’.

Chiang claimed that he had returned so that he might be of immediate service to Dr. Sun, however, when he arrived back in Shanghai, he didn’t report to Dr. Sun, but instead went home to Chekiang.

“Chiang had probably calculated that the unique experience and knowledge he had acquired on his mission to Russia had made him indispensable to the Kuomintang, and he was stubborn and extreme enough to make use of this fact to strengthen his position within the party before agreeing to proceed to Canton.” [The Early Chiang Kai-shek, by Pichon Loh, pg. 89]

Knowing that Dr. Sun was ‘ever in need of qualified military personnel’ and was wishing to have first-hand information of what was happening in Russia, Chiang remained at home for a whole month, and only after being promised that he would head the new military academy would Chiang finally go to see Dr. Sun ‘to report all matters and make plans for Sino-Soviet cooperation’.

Chiang arrived in Guangdong just in time for the Kuomintang’s First National Congress, where Dr. Sun’s reorganization of the Kuomintang upset some older members, and created suspicions among some overseas members about his alliance with the communists, that he had to explain:

“First, their suspicions of Russia were due to their living in imperialist countries, where they were drenched with anti-Russian propaganda … He then explained that the ‘Principle of the People’s Livelihood’ actually encompassed the doctrine of socialism, which in turn encompassed two lesser doctrines, communism and collectivism … There was no great difference between the Kuomintang’s principles and communism. Furthermore, the application of communism did not originate in Russia but in Hun Hsiu-chuan’s Taiping Heavenly Kingdom. Nor did Russia practice pure communism; what it had put into effect really was a policy of the people’s livelihood.” [Sun Yat-sen, by Martin Wilbur, pg. 192]

On January 30th 1924, the last day of the Kuomintang’s First National Congress, Dr. Sun proposed twenty-four persons for the Central Executive Committee – including three communists, and he proposed seventeen reserve members – including seven communists, one of whom was a young 30-year-old, named Mao Tse-tung.

It is extremely important to note the irony that at this moment, Mao was higher up, in the Kuomintang’s leadership structure than lowly Chiang!!! Not only that, but Mao’s station this hierarchy was approved by the party members.

Dr. Sun had seen something in Mao, that he hadn’t seen in Chiang. Chiang was never to be appointed to any political position in the Kuomintang, only to military positions.

During the Congress, Chiang had been appointed as the chairman of the Preparatory Committee of the Military Academy, and he had been also reappointed to the party’s Military Council. However, (lowly) Chiang abruptly resigned as chairman of the Preparatory Committee because “Chiang and the Soviet advisers differed substantially on important points concerning the curriculum and management of the academy” and Chiang, “indignant at Soviet objections to his plans and unable to exercise full authority as he would have it, tendered his resignation.” [The Early Chiang Kai-shek, by Pichon Loh, pg. 91]

And he sulked back home to Chekiang, again.

In a letter to Dr. Sun of March 2nd 1924, Chiang stated his reason for his resignation:

“Chiang then brought up the matter that must have been foremost in his mind, namely, the question of ‘new influences’ in the party”. [ibid, pg. 93]

Chiang would write letters to party leaders, that he “dismissed the sincerity of the Soviets in cooperating with the Kuomintang” [and] “moreover, he urged faithful party members to disagree with Sun Yat-sen if need be.”

“Spiritually and historically speaking, Mr. Sun’s task has succeeded; but the effective implementation of this task at the present time is the responsibility of all of us and not that of Mr. Sun alone. We ought not simply to acquiesce and let matters drift, nor should we allow him to insist on his own opinions at the expense of the integrity of his comrades.” [ibid, pg. 95]

So much for Chiang’s professed devotion to Dr. Sun – he was organizing for his replacement already! and for the counter-revolution!

Meanwhile as Chiang was in Chekiang, the Russian instructors, arms and funds were beginning to arrive, and Liao Chung-kai and a committee of seven began the planning and establishment of the military academy, and the selecting of the staff and examining all of the 3,000 applicants for the first 500 students.

Unfortunately, the first recruiters were jailed or killed by rival militarists, and the recruitment was largely done by Chen Kuo-fu, and so, a large part of the applicants were from the Green Gang!

By May, Chiang’s backers had succeeded in having him return, from his three-month staged tantrum, to Guangdong, to meet with Dr. Sun and to be appointed as the commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy, and also as the chief-of-staff to the Kwangtung Amy under the command of Hsu Ch’ung-chih.

Although Chiang was commandant at Whampoa, the cadets were taught by the Russian instructors, and also were taught by Chou En-lai, the director of the Academy’s Political Department.

But now we can begin see the real Chiang, someone who had never done anything in terms of the political campaigns, and had done very little in the military campaigns, as he continued to show his disdain of Dr. Sun’s leadership.

“During the next six months, until Sun’s departure for Peking on November 13, Chiang was to disagree with Sun on many issues and even to disobey orders in several instances … Their disagreement over this issue must have been a factor in influencing Chiang’s formal though not final resignation as commandant of the Whampoa Academy on September 16.” [ibid, pg. 96-97]

“In another instance, Dr. Sun wrote to Chiang on October 8 castigating him for his failure to apply to Whampoa the Soviet-inspired military organizational system Sun had personally drafted. His disgust with Chiang’s recalcitrance was evident in his statement that the rejection of his plan was a clear indication of the tradition-bound mentality of those ‘Japanese-trained cadets and Paoting officers who know very little and comprehend even less and who are totally ignorant of the general international situation’. Moreover, their disagreement over the Second Northern Expedition which Sun had launched on September 18 ran so deep that Chiang in fact disobeyed Sun’s direct orders to evacuate the Whampoa and indeed requested the recall of Whampoa cadets from front line duties.” [ibid, pg. 97-98]

Professor Loh concludes with this dismal prognosis of Chiang’s future, that “No suggestion is intended that Chiang would necessarily have been given more important assignments or entrusted with the primary responsibility for nation-building had Sun lived longer to preside over a more careful distribution of power among the leading party personalities.” [ibid, pg. 98-99]

Chiang wasn’t going much farther, unless something drastic happened!

Dr. Sun’s THREE Principles

The First National Congress of the Kuomintang was held from January 20th to 30th 1924, to begin to put together the framework and structure of the party – establishing the Central Executive Committee, and the eight Bureaus – for Organization, Propaganda, Youth, Labor, Farmers, Women, Overseas Chinese, Military Affairs and Investigation. This would lay the basis for organizing a national revolutionary movement among farmer organizations, labor unions, and also the workers and peasants.

But the news of Lenin’s death reached Guangdong, and the Congress sent a telegram of condolence to Soviet Russia and they adjourned for three days of mourning.

While that Congress was still ongoing, Dr. Sun began a lecture series starting on January 27th at the Guangdong Higher Normal School to educate the party cadre in his political philosophy the ‘San Min Zhuyi’ – the Three Principles of the People, that would form the basis of his revolution.

The first six lectures that he gave were on the first principle of ‘Nationalism’. After his lectures, the transcripts would be rushed into print to be distributed throughout China. Then, Dr. Sun began the next six lectures on March 9th on the second principle of ‘Democracy’.

After delivering the last lecture on principle of Democracy on April 26th, Dr. Sun became seriously ill, with some newspapers (like the New York Times) even reporting that he had died. But news of his death was perhaps just wishful thinking on their part, or as Mark Twain would have said, rumors of his death were grossly exaggerated. After recuperating for a month at Baiyunshan (White Cloud Mountain), Dr. Sun returned to Canton.

But during that time, a conflict was begun (by some people in Shanghai). One side demanded that the communists should be kicked out of the Kuomintang, and the other side then demanded that the communists should resign from the Kuomintang. Dr. Sun was able to keep his United Front together, when the Central Executive Committee decided that “… all who have entered the party and who display revolutionary determination and sincerely respect the real ideas of the Three Principles of the People shall be treated as party members, no matter what faction they belonged to previously … Comrades of the party should not be suspicious but should continue the former struggle.”

Dr. Sun’s revolution was to be based on his lectures of his Three Principles, and not on party factions and party standing, but upon ideas!

On August 3rd, to answer these attacks, Dr. Sun again began his lectures, this time on the third principle, the ‘Doctrine of Livelihood’, that an understanding of the old Chinese phrase ‘min sheng’ [people’s livelihood] would encompass ‘the problems of socialism, communism and cosmopolitanism’.

And he took up the problem of the ‘anti-communism’ of some of the members (and Chiang too) – that only following the doctrine of ‘nationalism’ and that somehow the principles of ‘democracy’ and ‘livelihood’ would follow along, is not enough.

“Our old comrades in the Kuomintang have often misunderstood the communist party. They believe that communism is contradictory to the San Min Doctrine. Twenty years ago, we organized ourselves together as supporters of the San Min Doctrine, although many among us were convinced that only the doctrine of nationalism was necessary to bring about the salvation of China.

For instance, the members of the Tung Ming Hui aimed only at the overthrow of the Manchu dynasty. Most of them would have been content after the overthrow of the Manchus if a Chinese had been made emperor. As a matter of fact, their nationalistic feeling fundamentally contradicted the doctrine of democracy, even though I had required them to take an oath adhering to the San Min Doctrine.

Some of the most thoughtful of our fellow-revolutionists were of the opinion that a realization of the meaning of the doctrines of democracy and livelihood would grow along with the realization of the meaning of nationalism. Consequently the doctrines of democracy and livelihood were not seriously studied, and were little understood …

The troubles have been due to lack of a clear understanding of the meaning of the doctrine of democracy on the part of the members of the Tung Ming Hui, and a greater lack of understanding of the doctrine of livelihood.”

Dr. Sun was only able to give four lectures on the doctrine of People’s Livelihood, even though he had more lectures planned, because he had to deal with an attack from the British Empire.

The British Opium Banksters’ Rebellion

On August 2nd, the day before he was to begin his lectures on the People’s Livelihood, Dr. Sun appointed his brother-in-law, T.V. Soong, a Harvard-trained economist, to be the first manager of the Central Bank of China (with the starting capital coming from a $10 million loan from Soviet Russia) that would be the government’s treasury, that would accept people’s deposits, and that would issue bonds and issue banknotes – to begin to wrestle control of the markets and currency, away from corrupt tax-collectors, the warlords, and especially the foreign powers.

Nooooooooo!!!, screeched the British Empire’s opium banksters, Nooooooooo!!!

“The Canton Chamber of Commerce was getting secret help from Great Britain to expand the Merchants’ Volunteer Force. Locally, the volunteers were sponsored primarily by the powerful head of the Chamber, Chen Lien-po of the Hong Kong-Shanghai Bank” [!!!] [The Soong Dynasty, by Sterling Seagrave, pg. 193]

A shipment from Amsterdam, of 5,000 rifles and 5,000 pistols (plus ammunition), that had been arranged by the Hong Kong-Shanghai Bank and the British commissioner of customs at Canton [Guangzhou], arrived in the harbor for the Merchants Volunteer Corps – made up of ‘disbanded soldiers, discharged policemen, city ruffians, [bandits] and bad characters, all hired for $12 a month’. [Sun Yat-sen, by Martin Wilbur, pg. 364]

The shipment was seized by the Kuomintang government, under orders from Dr. Sun, and placed under guard of Commandant Chiang and a small force at Whampoa.

The Canton [Guangzhou] merchants threatened to call for a general strike, Dr. Sun threatened to impose martial law, but the British Consul General, in a dispatch, threatened Dr. Sun that “in the event of Chinese authorities firing upon the city, immediate action is to be taken against them by all British Naval forces available”!!! [ibid, pg. 252]

Dr. Sun responded with a manifesto that “… charged British imperialism with supporting the rebellion of the comprador of the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, and called the threat in the British consul’s dispatch tantamount to a declaration of war.

It derided British concern over the ‘barbarity of firing on a defenseless city’ as hypocrisy ‘in light of the Singapore Massacre, Amritsar, and other atrocities in Egypt and Ireland’.[!] Dr. Sun repudiated the suggestion that his government could fire on a defenseless city, since the only section of Canton against which it might be compelled to take action was Hsi-kuan, the armed stronghold of the Chen Lien-po rebels.” [ibid, pg. 252]

And then, Dr. Sun declared an ‘anti-imperialism week’ with a rally and parade.

“The turmoil and poverty in this country, although in natural resources we are perhaps the richest in the world, is due to one cause, namely that our international status is worse than that of a colony … Hence we have many masters, pursuing their sinister objectives in devious ways: some ruthlessly, some cunningly, some openly, some under the guise of benevolence, some supported by powerful navies to break into our house, some kindly propose to keep open our door. But all together IMPERIALISM has but one aim – to keep us down economically and politically.” [ibid, pg. 253]

After weeks of negotiation, an agreement was worked out for the return of the rifles to the Merchants Corps, for which they would give $200,000 and a pledge of fealty.

On October 10th, there was a parade to celebrate the anniversary of the 1911 revolution, and when the parade reached the place at the waterfront where the arms were being transferred to the Merchants’ Corps, pushing and shoving between the different groups ended in a street battle, where some of the Merchants Corps fired on marchers – a dozen paraders were killed, and many spectators were killed or wounded.

The Merchants’ Corps claimed that they had only received half of their rifles and so they called a general strike, barricaded the streets of the Hsi-kuan suburb, and put up posters calling for the overthrow of Dr. Sun’s government. Dr. Sun brought 5,000 troops (from his Northern Expedition force at the East River) into the city, declared martial law, and set up a Revolutionary Committee to deal with the crisis.

At dawn on October 15th, the Nationalist forces raided the barricaded Hsi-kuan suburb, along with 800 Whampoa cadets, 220 cadets from the Hunan military school, 500 cadets from the Yunnan military school, 250 troops from armored trains, 2,000 policemen, and 320 Workers’ Militia and Peasants’ Corps – trained by instructor Mao Tse-tung. [Seagrave, pg. 195-196]

There is no mention of Chiang, and the Whampoa cadets that had guarded the arms, as participating in the battle. “Chiang Kai-shek’s name appears only in later Nationalist accounts.” [Wilbur, pg. 365]

When the Corpsmen began firing down on the government troops from the towers of the storehouses, these buildings were then set on fire by government saboteurs, and an estimated 490 houses were burned. The defeated Corpsmen were disarmed, while their leaders fled to the British at Hong Kong.

And as the rebellion was ended, the British Empire’s opium banksters stopped their screeching … for now.

‘What is under heaven, is for all’

By September 1924, after narrowly avoiding a threatened British naval attack during the strike of the Merchants Corps, Dr. Sun had decided that the long-delayed Northern Expedition against the warlords in Beijing, must be started immediately.

In a letter to Chiang, Dr. Sun stated his reason that “During this strike, if we had delayed a day longer a conflict would surely have emerged, and the objectives of the English gunboats would have been my headquarters, the gunboat Yung Feng, and Whampoa – which could have been pulverized in a few minutes. We absolutely do not have the power to resist them … we cannot continue to stay in this place another moment; therefore it is best to relinquish it quickly, leave completely, and plan a different road to life. The very best road to life now is through a Northern Expedition.” [Sun Yat-sen, by Martin Wilbur, pg. 254-5]

Chiang’s response to Dr. Sun’s northern expedition would be ‘to petition to resign his position as commandant of the military academy’. [ibid. pg. 256]

Note: The late author, Lee Ao, whose books were banned in Taiwan, showed of the 14 times, from July 31st 1918 to February 21st 1924, that:

“Chiang Kai-shek had either quit the jobs, or deserted the posts, or resigned his work, with the first occurrence being the 7/31/1918 quitting the ‘tactician’ job under Chen Jiongming [after four months’ service] and the last occurrence being the 2/21/1924 quitting the Whampoa academy preparatory committee due to Sun Yat-sen’s plan in assigning the ‘principal’ job onto Xu Chongzhi.”

[Could this be called number 15, perhaps?]

Meanwhile, during the current war between the Zhili warlord clique (backed by Britain and America) and the Fengtian warlord clique (backed by Japan), a Zhili general, Feng Yu-hsiang, switched sides, and carried out a successful coup to capture the capital, Beijing. Feng arrested Cao Kun, the president, kicked the emperor PuYi out of the forbidden city, dissolved the National Assembly, set up an interim administration, and invited Dr. Sun to come to Beijing to help with national reunification and to meet with him and with Chang Tso-lin (Fengtian clique warlord), and Tuan Chi-jui (Anhui clique warlord) – the new interim chief executive.

Note: When Feng died in 1948, Mao would classify Feng as a ‘good warlord’, and allowed Feng to be buried at Mount Tai, Shandong.

Now, Dr. Sun’s ‘Northern Expedition’ was stopped, and his ‘Northern Trip’ was begun. Dr. Sun proposed the convening of a newly elected National Assembly and the ending of all the un-equal treaties.

Before he left Guangdong, he appointed Hu Han-min as Acting Grand Marshall of the Revolutionary Government, Tan Yen-kai in charge of the Northern Expedition, and Hsu Chung-chih as head of the Military Affairs, with (lowly) Chiang as his secretary.

Dr. Sun did not meet with any of the the British or Americans, but instead he sailed to Kobe, Japan for six days of meetings – to try to convince Japan of the correct policy of abolishing the un-equal treaties, and of helping China to gain its independence.

Dr. Sun would say to Japan that “Now, the question remains whether Japan will be the hawk of the Western civilization … or the tower of strength of the Orient.” [Soong Dynasty, by Sterling Seagrave, pg. 199]

One could perhaps ask Japan the same question again today – 100 years later!

The other foreign powers were demanding the recognition of the un-equal treaties as the price to pay for international recognition of a new government, and also demanding they take a stand against Dr. Sun’s ‘pro-Bolshevik’ activities.

But upon arriving back in China from Kobe, the 58-year-old Dr. Sun fell very ill but never recovered, dying on March 12th 1925. As he had wanted, he would be buried in Nanjing, near the tomb of the first Ming Emperor, at Zijin Shan [Purple Mountain], with Dr. Sun’s motto – ‘What is under heaven is for all.’

Dr. Sun had been the one person could command the respect of the various political personalities and factions within the Kuomintang party and the Guangdong revolutionary government, and also within the various warlord military personalities and factions – as he attempted to point them in the right direction. With his death and the loss of his genius, the intricate balancing-act might again rest upon military power.

At Guangdong, that rested on the military forces under Hsu Chung-chih, Tan Yen-kai, Chu Pei-te and the small force from the Whampoa Academy, that was loyal to Commandant Chiang Kai-shek.

Without Dr. Sun’s leadership, the interim government in Beijing under Tuan, would bow down to the foreign powers and agree to honor the old un-equal treaties. And in obedience to the foreign powers, a purge would soon be launched against the small group of communists in the Kuomintang, who had committed no crime, except perhaps the crime of being in the way?

And what would become of Dr. Sun’s brilliant ‘United Front’ strategy to defeat colonialism?

Note: I find it very curious and intriguing to look at China’s Belt and Road Initiative of today as a new ‘United Front’ strategy to defeat the continuing colonialism of the North Atlantean opium-war banksters.

The Rising Tide Foundation is a non-profit organization based in Montreal, Canada, focused on facilitating greater bridges between east and west while also providing a service that includes geopolitical analysis, research in the arts, philosophy, sciences and history. Consider supporting our work by subscribing to our substack page and picking up some Rising Tide Foundation merchandise!

Also watch for free our RTF Docu-Series “Escaping Calypso’s Island: A Journey Out of Our Green Delusion.”

Fascinating reading .

Thanks for an interesting post.

Where did you get that excellent map of a divided China around the time of Sun's death? Did you make it?